After the 2022 Grammy winners were announced in early April, I finally took the time to listen to the Foo Fighters’ Medicine at Midnight, which is definitely a recording worthy of its award for Best Rock Album and also definitely worth your time and ears. But it dawned on me that, even after 25 years, I never owned a (CD? record? file?) of my favorite Foo number of all time, the one that for me sets the gold standard for all other Foo charts past, present, and future: Everlong. So I downloaded it, and over the past few weeks, I’ve looped it in my car several dozen times.

You may have read my blather elsewhere about how I remember where I was when I first heard different pieces of music. The first time I heard Everlong, it was the early autumn of 1997; I had finished grad school but was still living in Chicago, and I was on my way downtown for a Civic rehearsal. I was at a stoplight, looking at a building through the open moonroof of Chuck—my dark blue, “wood”-paneled Jeep Grand Wagoneer that broke down more than once on Lake Shore Drive. Chuck had charisma but that’s about all.

Below is a kind of “form and analysis” version of why this tune sticks with me. It’s not about the lyrics—I know that lyrics are key for most, probably especially for Dave Grohl, but for me, they’re secondary on this one, and I’ll leave it to Grohl, himself, to explain the text. I haven’t done a deep dive like this on a piece since college, and it was either Mozart 40 or the Brahms A Major Intermezzo, so a Foo Fighters tune will be a first. This is less a scholarly presentation and more like an unordered list, but maybe that makes for quicker reading. Before that, have a listen:

I should mention that in the studio release (which was the second single off their second album, The Colour and the Shape) Grohl plays both guitar and drums in addition to singing; Taylor Hawkins, who appears in the bizarre video with Grohl, was not yet officially the band’s drummer when the studio recording was made. The other musicians are guitarist Pat Smear and bassist Nate Mendel. Louise Post of the band Veruca Salt, Grohl’s girlfriend at the time, sings harmonies but is uncredited.

Enough intro. Why do I like Everlong so much? Let’s have a look:

Fast music over slow changes

For me, the distinguishing mark is that there are three different strata of tempi in Everlong:

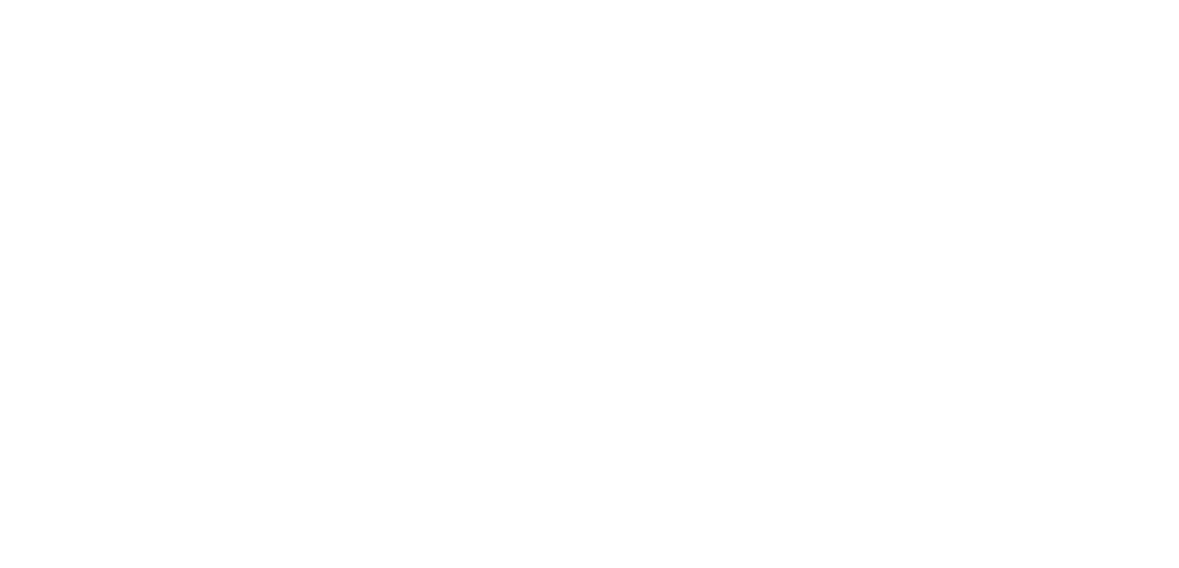

- a rhythmic tempo in 4/4 time (provided by the rhythm guitar and drums—particularly the high-hat, with its persistent sixteenth-note drive)

- a lyric tempo which, for the verses, is felt in 2/2 time and therefore feels half as slow as the rhythmic tempo

- a harmonic tempo (i.e., the tempo of the chord progression, or “changes” in jazz parlance) that is half as slow again.

Set your metronomes:

- Rhythmic: 154 bpm

- Lyric: 77 bpm

- Harmonic: 38 bpm, on average, but this is flexible and accords to the form.

A centuries-old form…

Everlong in formal terms is a modified verse-chorus form, and I’d argue—from the standpoint of harmonic rhythm—that it is also an isorhythmic motet, a medieval form that features a repeating line in one or more voices. The overall structure is:

- Introduction

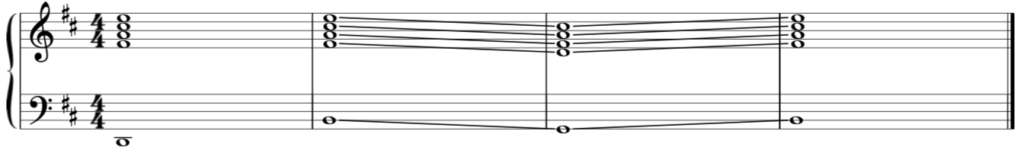

- Pre-verse* / Verse 1

Hello, I’ve waited here for you… - Pre-verse / Verse 2

Come down, and waste away with me… - Pre-chorus 1 / Chorus 1

And I wonder… / If everything could ever… - Pre-verse / Verse 3

Breathe out, so I can breathe you in… - Pre-chorus 2 / Chorus 2

And I wonder… / If everything could ever… - Break

- Pre-chorus 3 / Chorus 3

And I wonder… / If everything could ever…

*There is no such thing as a pre-verse, but that’s what I’m calling it. Here, it’s a wordless section of music similar to the intro, but there is a difference in the rhythm guitar and the kickdrum that makes it distinct and helps to set up the verses. More about that later.

…with a twentieth-century twist.

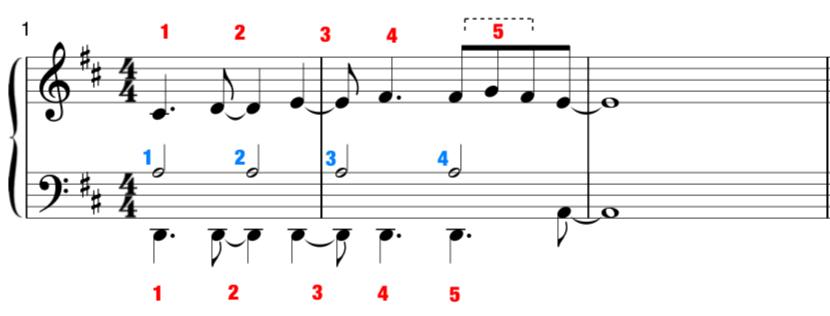

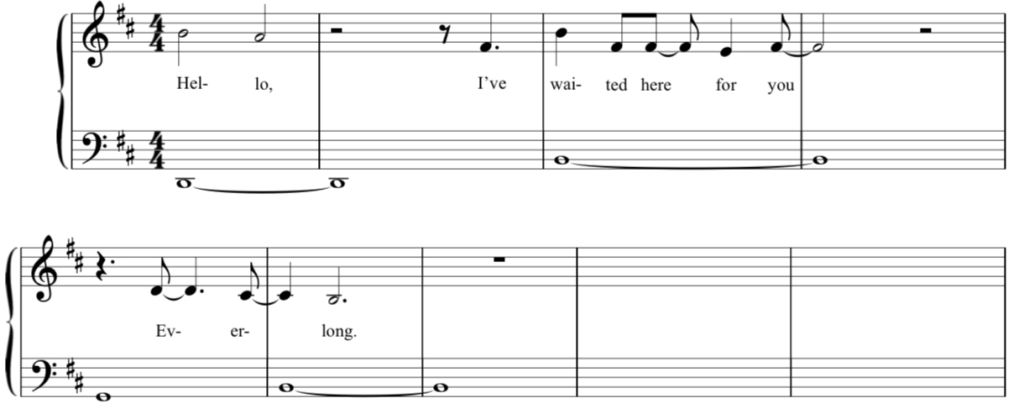

This verse-chorus form, akin to rondo form, makes for nice, even symmetry. Further, what we’ve come to expect from rock music over the decades is an even, 4/4 or 2/2 time, in groups of four or eight measures each. Everlong, despite its 4/4ness, is anything but square. I’m not sure of Grohl’s intent—whether it’s a function of the delivery of the text or a reflection upon the text itself—but Everlong makes great use of odd numbers and asymmetry. The intro, pre-verses, verses, and the break are all seven-bar phrases. The pre-choruses are in three-bar phrases. Within those three-bar phrases are quasi-hemiola syncopations (played by guitars and bass) that are five-against-four in the first two bars, with the remaining bar each time setting up the next phrase:

Interestingly, there is a similarity in length (14 measures) among the pre-verse/verse sections and choruses, but those fourteen measures are achieved in different ways: 7+7 for the pre-verse/verse sections, and 4+4+6 for the choruses.

Harmony, harmonic contour, and harmonic rhythm

Everlong is, by and large, a three-chord chart. Very occasionally does it employ a fourth chord. The song doesn’t stray from the harmony that exemplified the doo-wop songs of the 1950s. What makes Everlong unique, though, is the particular coloring of the chords and how they are ordered. The Colour and the Shape.

Everlong’s distinct sound color owes to a few things: its chord extensions (pitches added above the standard chord) and common tones (pitches shared from chord to chord), its harmonic contour (the profile shape of the chord changes), and also what’s called “parallel motion” between some chords. There’s also an interesting detail in the harmonic rhythm—how the chord progression is distributed across time.

Harmony

The song centers around D major, using the following chords (I’ll use “fake book” notation for simplicity). Tap the pitches to hear how their sounds build these chords — with an amazingly bad MIDI version of “Distortion Guitar!”

DMaj7 (I)

Bsus9 (vi)

Gsus9 (IV)

A5 (V) just an open-fifth of an A and an E. Used sparingly, during the pre-choruses only.

Common Tones and Extensions

The DMaj7 chord that opens the song, for example, changes such that the D is replaced by a B in measure 3 to create a Bsus9 chord: the C# that was the major “seventh” of DMaj7 becomes the “ninth,” suspended above B; the A which was the “fifth” becomes a “seventh,” and so on. Most of those pitches (minus the C#) are then common to the Gsus9 in measure 5. The distortion guitar enters in measure 8 with whole notes to reinforce the harmony, but by measure 15 (Pre-verse 1) it settles into a rhythmic groove and adds an E—a further chord extension—creating DMaj7/9, Bsus9/11, and Gsus9/13. Already we’re pretty far from a doo-wop sound.

Harmonic Contour

The harmonic contour also lends to this song’s signature quality. Using this D major key for sake of argument, a frequently used chord progression in pop music would be D—Bmi—G—A (known as the “50s progression” and repeated ad nauseum in the case of doo-wop) but Grohl tricks us in the pre-verses and verses by making a wider leap after G, returning to B minor instead of A.*

Foo Fighters bassist Nate Mendel adds interest to this progression by ascending a major sixth from D to B above, rather than taking the expected descending minor third from D to B below. The choruses themselves play the verse progression in a unique inversion: Bsus9—Gsus9—D. That resolution from G to D is technically called a “plagal cadence” or “amen” cadence, because it sounds like the end of a hymn. Everlong’s unusual harmonic contour culminates with an unresolved G chord, known as a “plagal half-cadence.”

*Side Note: this movement, D—Bsus—Gsus—Bsus, without changing the way the chords are voiced (i.e. “stacked”) is intriguing because it creates parallel motion. A hallmark sound of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, parallel motion (especially between chords with fifths) became a big no-no by the Baroque and Classical periods, but the Seattle grunge sound capitalized on it.

Harmonic Rhythm

There is an interesting detail about the harmonic rhythm of this song as it relates to the melodic rhythm of the lyrics. During the pre-verses and the verses, harmonic movement is made on strong, “count 1” downbeats only, which is contrary to the rhythm of the melody which is quite syncopated with accents on the off-beats:

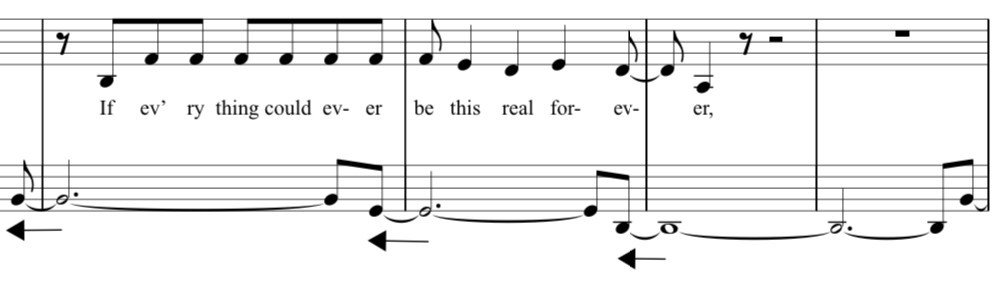

In the choruses, however, the harmonic rhythm is shifted one eighth-note to the left, so that the chords anticipate the downbeats. This shift acts like a propellant, helping to drive the music and keep it moving forward, as the melody becomes more syncopated and blurs the bar line:

Drumming

Quite simply, the drums are the anchor of this chart. Dave Grohl’s unwavering time and attention to detail are impeccable. Grohl evokes many different colors from the set and uses them to delineate the form, touring us through the work while also helping himself as vocalist. (I’m making a presumption there—I can’t be sure but I’d venture a guess that he recorded the drum track before recording the vocals.)

Here are just a few examples of these details, in no particular order:

The main character for the drum set in Everlong is undeniably the high-hat playing a relentless drive of sixteenths that makes my forearms sore just to hear. The snare is holding us to the rails on counts two and four and the kick drum outlines the downbeats. But a single stroke of the ride cymbal smartly outlines each turn of the seven-bar verses and pre-verses.

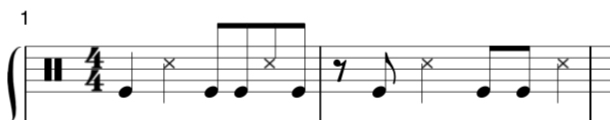

I mentioned earlier a difference in drumming between the pre-verses and verses. During the pre-verses, Grohl uses solid, straight quarter notes and allows more space for the the guitar, which is also mostly playing quarters with the exception of a distinctive eighth-note pattern on count three of every other bar:

During the verses, the snare remains solidly on counts two and four of each measure, but Grohl plays a lilting rhythm in the kick drum that adds interest and helps to guide the syncopated rhythm of the melody:

During the pre-choruses and choruses, Grohl plays incredibly complex fills on the snare and toms but never gets lost in the time. All phrases and sections seamlessly match end to end.

Grohl sometimes uses the pedal to open the high-hat (rather than just hitting it harder) for crescendos leading from section to section, and uses the different perceivable pitches between toms and snare to achieve similar crescendos.

Conclusion

There’s not really a conclusion here, since there is no real order or argument in the above text. Just enjoy Everlong, both for its simplicity and its complexity, and see if you listen to it and other songs differently next time.